Currently I am working on a research on the Feyenoord Stadium in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. People form Rotterdam use to call it "de Kuip". I many respects I should be considered as one of the most important remains of the functionalist movement. The building is designed by Brinkman and Van der Vlugt, who also designed the famous Van Nelle factory in Rotterdam. The building was completed in 1936, a few months after the early death of Leendert van der Vlugt. Unfortuanally the building nowadays does not show its groundbreaking features anymore, especially from the outer facade lost its modernist transparency and lightness. Important features of the building: The free-floating second ring without supporting columns at the end. The main construction on the outside, completely visible. Emphasized are the 22 staircase because the movement of the crowd had to be shown; the building is a machine. And off course, the industrial apparance is also a reference to the cranes and ships in the harbors of Rotterdam.

The pictures here below all come from the Dutch magazine Bouwkundig Weekblad, published in 1936.

Friday, December 9, 2011

Queen Europe

Recently I visited Prague where I found in one of the museums this interesting representation of Europe, depicted as a queen. I shows Bohemia, Prague as the very heart of Europe, Portugal as the crown and Spain as the face. The right hand holds a orb, symbolizing the domination over the world, probably by the Catholic Church. Sadly enough, my poor little country The Netherlands is not even mentioned on the map.

If you want to know more about this map, check out the very interesting information on wikipedia.org.

It would be interesting if someone would draw such representation of contemporary Europe in its current crisis.

If you want to know more about this map, check out the very interesting information on wikipedia.org.

It would be interesting if someone would draw such representation of contemporary Europe in its current crisis.

Friday, November 18, 2011

Slum proportion in Africa, Latin America and Asia

I came across these maps of Africa, Latin America and Asia in the recent UN-report State of the World's cities 2010/2011: bridging the urban divide. I don't think these maps need any explanation.

Labels:

africa,

asia,

latin america,

Slum,

urban informality

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Property, scarcity and urban informality (DRAFT)

Locke’s theory of property can only fully be understood in relation to the colonization of the newly discovered American continent. His idea is that appropriation of land should take place by cultivating the land; the uncultivated land did not belong to anyone. The native Americans did not own the land because they were only hunter gatherers. The more one cultivates the more one legally owns.

According to Hans Achterhuis in his study on scarcity the influence of Locke’s theories of property can be considered as the legitemization of the capitalist concept of property. However, it also influenced early socialist and anarchist movements (Achterhuis, 1988, p. 71). One of the most influential anarchist thinkers, Peter Kropotkin, in his Anarchist Manifesto (1887) – not mentioned by Achterhuis – had a comparable concept of property: the producer of an product is automatically the legitimate owner (Kropotkin, 1970).

John Turner, who was one of the most influential figures in the debate on informal urbanization during, derived his ideas on what he called ‘squatter settlements’ for an important part from anarchist theories. Turner worked in the 1950s in Lima’s barriadas. These were settlements in the empty desserts around the capital of Peru were land was as even less uncultivated as during the colonization of North America. The concept of appropriation through cultivated, in this case urbanization was not such a bad idea.

However, this become very different in a situation of scarcity. Strangely enough this receives very little attention in Turner’s work. Achterhuis, in Het rijk van de schaarste, takes scarecty as a point of departure. Scarcity leads to conflict. (To finish later…)

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

The necessity of fallacies and distastefulness in the public debate

For anyone who lives in a liberal society it is obvious that we defend the freedom of the expression of opinion and the freedom of discussion. However, if someone asks us to give rational arguments to underpin these important values of liberal democracies, it could be difficult to give a clear answer. Certainly, freedom of speech is an individual’s right; everyone should be able to say whatever he or she wants, even if the message is unpleasant, controversial or even shocking. In this article I do not want to discuss the limitation of freedom of speech and expression, but to adduce arguments in favor of the widest possible performance of these freedoms.

One might wonder why it is necessary to bring these arguments forward. Almost all of the readers of this blog would utterly agree with me when I state that the freedom of expression of opinion is something worth fighting for.

However, I would argue that the necessity for examining the importance of the freedom of speech become more clear if we look cases where the political and intellectual establishment almost unanimously agrees on the distastefulness of the expressed opinions. In the Netherlands the politician Geert Wilders was accused of hate speech and the insulting of religious groups; he was acquitted of all charges after a careless trail in June 2011. Another example are the activities of the fundamentalist preacher Terry Jones, who planned a “International Burn a Koran Day”. What I noticed was that one aspect of the freedom of expression received little attention: that also opinions and expressions which are distasteful, untrue, or even stupid contribute to truth and freedom.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1973) summarizes in his essay On Liberty, first published in 1859, the most important arguments why freedom of discussion and freedom of expression are so important. The first ‘ground’ for always allowing the freedom of opinion and the freedom of expression of opinion is because the silenced opinion of the dissident is possibly true. According to Mill nobody is infallible, and therefore we should always be open for discussion.

Secondly, and more common, is a situation where the silenced opinion is untrue ‘contains a portion of truth’ but is not the whole truth. By opposing opinions the truth might come to light.

Thirdly, the expressed opinion could be the ‘whole truth’. But even if the opinion is the whole truth it needs to be ‘vigorously and earnestly contested’. By extensively discussing a true opinion we understand its ‘rational grounds’, Stuart Mill argues.

And fourthly, Mill warns against the transformation of truth into dogma. Without ‘real and heartfelt conviction’ we might lose the meaning of the doctrine itself, only through personal examination truth can remain vital and effective. If people express untrue opinions are, Mill argues, it will result in ‘clearer perception and livelier impression of truth’. ‘Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post, as soon as there is no enemy in the field.’ Truth needs the collision with error in order to present itself. Without this collision the ‘living truth’ becomes a ‘death dogma’.

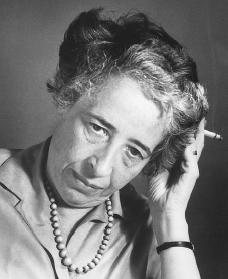

In John Stuart Mill’s work the discussion and debate should lead to truth, and the discussion is not a goal in itself. Free discussion is functional and necessary because leads to truth. Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), another important political philosopher who extensively wrote about freedom, has a different understanding of this issue. For Arendt the free discussion among citizens is itself a manifestation of freedom, in other words, a public debate is itself the performance of freedom. Freedom is like music: as long as the musicians play their instrument there is music; as long as we speak, debate, and act in public there is freedom. In the essay On Freedom (1960) she states that the raison d’être of these ongoing discussions and public debates –Arendt calls this politics – is to ‘establish and keep in existence a space where freedom as virtuosity can appear. This is the realm where freedom is a worldly reality, tangible in words which can be heard, in deeds which can be seen.’

Following Arendt’s argumentation it is not so much the outcome of the free discussion (truth), but in the first place the performance of freedom which is important. The silencing of debate does not only deprive a society of the truth that might emerge from it, but more crucial, it results in the extinguishing of freedom. The collision between opinions, collision between truth and error is itself a manifestation of freedom. The fact that we as free citizens can speak in public about all sorts of things happing in our society determines our freedom.

Following Arendt’s argumentation it is not so much the outcome of the free discussion (truth), but in the first place the performance of freedom which is important. The silencing of debate does not only deprive a society of the truth that might emerge from it, but more crucial, it results in the extinguishing of freedom. The collision between opinions, collision between truth and error is itself a manifestation of freedom. The fact that we as free citizens can speak in public about all sorts of things happing in our society determines our freedom.

Terry Jones and Geert Wilders are not thus essential players: in the antagonism of the public realm truth and freedom can manifest itself.

Arendt, H. (1960) What Is Freedom? In: P. Baehr, ed. (2000) The Portable Hannah Arendt. New York: Penguin Books, pp. 438-461.

Stuart Mill, J. (1859) [2010] On Liberty. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 25-80.

Labels:

debate,

discussion,

freedom,

Geert Wilders,

Hannah Arendt,

John Stuart Mill,

liberty,

on freedom,

on liberty,

Terry Jones,

truth

Saturday, March 13, 2010

René Girard - Violence and the Sacred

Interesting fragments about circles of violence, from René Girards influential book Violence and the Sacred (1972).

“The fear generated by the kill-or-be-killed syndrome, the tendency to “anticipate” violence by lashing the first (akin to our contemporary concept of “preventative war”) cannot be explained in purely psychological terms. The notion of a sacrificial crisis is designed to dissipate the psychological illusion; even in those instances when Henry borrows the language of psychology, it is clear that he does not share the illusion. In a universe both deprived of any transcendental code of justice and exposed to violence, everybody has reason to fear the worst. The difference between a projection of one’s own paranoia and an objective evaluation of circumstances has been worn away.” (p. 54.)

“The mechanism of reciprocal violence can be described as a vicious circle. Once a community enters the circle, it is unable to extricate itself. We can define this circle in terms of vengeance and reprisals, and we can offer diverse psychological descriptions of the reactions. As long as a working capital of accumulated hatred and suspicion exists at the center of the community, it will continue to increase no matter what men do. Each person prepares himself for the probable aggression of his neighbors and interprets his neighbor’s preparations as confirmations of the latter’s aggressiveness. In more general terms, the mimetic character of violence is so intense that once violence is installed in a community, it cannot burn itself out.

To escape from the circle it is first necessary to remove from the scene all those forms of violence that tend to become self-propagating and to spawn new, imitative forms.

When a community succeeds in convincing itself that one alone of its numbers is responsible for the violent mimesis besetting it; when it is able to view this member as the single “polluted” enemy who is contaminating the rest; and when the citizens are truly unanimous in this conviction – then the belief becomes reality, for there will no longer exist elsewhere in the community a form of violence to be followed or opposed, which is to say, imitated and propagated. In destroying the surrogate victim, men believe that they are ridding themselves of some present ill. And indeed they are, for they are effectively doing away with those forms of violence that beguile the imagination and provoke emulation.” (p. 81, 82)

Girard, R. (1977) Violence and the Sacred, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Oscar Niemeyer

Uit: Close up: Oscar Niemeyer – het leven is een ademtocht

"Zo besloten we in Brasilia eens ’s avonds laat naar ’t Alvorada te gaan kijken, toen dat net klaar was. We kwamen aan en waren verrast hoe mooi het was. Het leek net een beeld, zonder enig doel, behalve z’n eigen pracht. Ik zei: ‘Dit is zo’n moment dat architectuur wordt geboren.’ Architectuur is een nieuwe, andere vorm, die dient te verrassen.

Het gaat om vrijheid in de breedste zin van het woord. Er moet sprake zijn van verbeelding, andere oplossingen. Dat is wat belangrijk is in architectuur. Wat er overblijft zijn niet de keurig onderhouden huisjes. Dat zijn de kathedralen, de koepels, het grote evenwicht. Schoonheid is belangrijk, neem de piramides. Die zijn zo mooi en monumentaal dat je de eigenlijke functie vergeet. Je bewonderd ze alleen maar. Als je alleen maar aan de functie van iets denkt, wordt het niets. (…) Als ik openbare gebouwen ontwerp, zoals die drie in Brasilia probeer ik iets moois, anders en verrassends te maken. Ik weet dat arme mensen er niets aan zullen hebben. Maar ze kunnen wel kijken en ervan genieten, verrast zijn door het nieuwe. Op die manier kan architectuur zin hebben. Ze kan haar doel alleen bereiken via een humaan, sociaal beleid. Architectuur is voor lui met geld. In de favela’s blijven ze de pineut. Hier staat mijn motto. [Wijst naar een sculptuur op zijn bureau. JvB] Zie je dat figuurtje daar bovenin? Dat rode ding? Daar staat: Als je de klos bent kun je het wel vergeten."

"Voor mij was de belangrijkste uitspraak van Le Corbusier: ‘Architectuur is uitvinden’. Dat begreep ik pas later, na een aantal boeken. Zoals die Franse dichter, ik weet zijn naam even niet meer. Die zij dat uitvinden, je verbazen het voornaamste kenmerk van de kunst is. Bij wat ik doe gaat het me bovenal om oorspronkelijkheid. Dat mensen stilstaan en verrast worden door iets nieuws. Baudelaire."

Labels:

Alvorada,

architecture,

art,

Baudelaire,

beauty,

favela,

freedom,

invention,

kunst,

Le Corbusier,

Oscar Niemeyer,

poverty,

public building,

suprise,

uitvinden,

verrassen

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)