For anyone who lives in a liberal society it is obvious that we defend the freedom of the expression of opinion and the freedom of discussion. However, if someone asks us to give rational arguments to underpin these important values of liberal democracies, it could be difficult to give a clear answer. Certainly, freedom of speech is an individual’s right; everyone should be able to say whatever he or she wants, even if the message is unpleasant, controversial or even shocking. In this article I do not want to discuss the limitation of freedom of speech and expression, but to adduce arguments in favor of the widest possible performance of these freedoms.

One might wonder why it is necessary to bring these arguments forward. Almost all of the readers of this blog would utterly agree with me when I state that the freedom of expression of opinion is something worth fighting for.

However, I would argue that the necessity for examining the importance of the freedom of speech become more clear if we look cases where the political and intellectual establishment almost unanimously agrees on the distastefulness of the expressed opinions. In the Netherlands the politician Geert Wilders was accused of hate speech and the insulting of religious groups; he was acquitted of all charges after a careless trail in June 2011. Another example are the activities of the fundamentalist preacher Terry Jones, who planned a “International Burn a Koran Day”. What I noticed was that one aspect of the freedom of expression received little attention: that also opinions and expressions which are distasteful, untrue, or even stupid contribute to truth and freedom.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1973) summarizes in his essay On Liberty, first published in 1859, the most important arguments why freedom of discussion and freedom of expression are so important. The first ‘ground’ for always allowing the freedom of opinion and the freedom of expression of opinion is because the silenced opinion of the dissident is possibly true. According to Mill nobody is infallible, and therefore we should always be open for discussion.

Secondly, and more common, is a situation where the silenced opinion is untrue ‘contains a portion of truth’ but is not the whole truth. By opposing opinions the truth might come to light.

Thirdly, the expressed opinion could be the ‘whole truth’. But even if the opinion is the whole truth it needs to be ‘vigorously and earnestly contested’. By extensively discussing a true opinion we understand its ‘rational grounds’, Stuart Mill argues.

And fourthly, Mill warns against the transformation of truth into dogma. Without ‘real and heartfelt conviction’ we might lose the meaning of the doctrine itself, only through personal examination truth can remain vital and effective. If people express untrue opinions are, Mill argues, it will result in ‘clearer perception and livelier impression of truth’. ‘Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post, as soon as there is no enemy in the field.’ Truth needs the collision with error in order to present itself. Without this collision the ‘living truth’ becomes a ‘death dogma’.

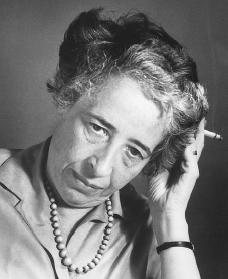

In John Stuart Mill’s work the discussion and debate should lead to truth, and the discussion is not a goal in itself. Free discussion is functional and necessary because leads to truth. Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), another important political philosopher who extensively wrote about freedom, has a different understanding of this issue. For Arendt the free discussion among citizens is itself a manifestation of freedom, in other words, a public debate is itself the performance of freedom. Freedom is like music: as long as the musicians play their instrument there is music; as long as we speak, debate, and act in public there is freedom. In the essay On Freedom (1960) she states that the raison d’être of these ongoing discussions and public debates –Arendt calls this politics – is to ‘establish and keep in existence a space where freedom as virtuosity can appear. This is the realm where freedom is a worldly reality, tangible in words which can be heard, in deeds which can be seen.’

Following Arendt’s argumentation it is not so much the outcome of the free discussion (truth), but in the first place the performance of freedom which is important. The silencing of debate does not only deprive a society of the truth that might emerge from it, but more crucial, it results in the extinguishing of freedom. The collision between opinions, collision between truth and error is itself a manifestation of freedom. The fact that we as free citizens can speak in public about all sorts of things happing in our society determines our freedom.

Following Arendt’s argumentation it is not so much the outcome of the free discussion (truth), but in the first place the performance of freedom which is important. The silencing of debate does not only deprive a society of the truth that might emerge from it, but more crucial, it results in the extinguishing of freedom. The collision between opinions, collision between truth and error is itself a manifestation of freedom. The fact that we as free citizens can speak in public about all sorts of things happing in our society determines our freedom.

Terry Jones and Geert Wilders are not thus essential players: in the antagonism of the public realm truth and freedom can manifest itself.

Arendt, H. (1960) What Is Freedom? In: P. Baehr, ed. (2000) The Portable Hannah Arendt. New York: Penguin Books, pp. 438-461.

Stuart Mill, J. (1859) [2010] On Liberty. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 25-80.